Reitz, South Africa (CNN)Danie Slabbert points toward the cattle that brought his farm back to life. Down the slope ahead of him, 500 black Drakensberger and mottled Nguni cows graze cheek by jowl.

The Free State farmer gestures with his giant shepherd’s crook.

«If cattle are part of nature, like they are now, then my cows are keeping the system alive,» he says. «How could you think that meat is the problem?»

Calls for plant-based diets to save the planet from the climate crisis are growing louder. But there is another, quieter, revolution reshaping the agricultural world. Farmers like Slabbert and their supporters say that what people eat is not as important as how they farm. They believe cattle and cropland could help save the planet.

«I have become a steward of this land and the cows are the key,» Slabbert says.

Mimicking the migration

Before settlers arrived with their guns and wagons, this part of what is now South Africa’s Free State province was an immense grassland. More than 30 species of grass anchored the rolling plains; fodder for millions of migrating antelope.

Over time, the wild herds were shot out and much of the plains became corn and potato fields.

There is still plenty of grassland here, or veld, as South Africans call it. Farmers such as Slabbert are looking back to those immense herds to recreate the natural cycle.

«What we are doing is trying to mimic nature,» he says, explaining that 200 years ago, huge herds of animals would have moved over this veld, avoiding predators in their tightly packed groups.»

Slabbert says he has rejuvenated the land by drastically increasing his cattle herd. He hems the animals into a rectangular patch of grassland with a low-current wire. For several hours, they eat all of the grasses they can find before the wire lifts, and the cattle rapidly move into a new section.

They are always moving, never selectively eating, just like a migratory herd. The method is called ultra-high density grazing. «These cattle are replenishing the land,» Slabbert says.

As they eat, the cows do what livestock do. Slabbert kneels down, pulls apart a pile of cow dung, and tenderly picks out a beetle. It lies dormant for a second, then uncurls its legs and strolls across his hand.

«These guys are one of the heroes of the story,» he says, as he gingerly places the dung beetle into its hole. The small insects break up the dung, the big ones haul the natural fertilizer deeper into the soil.

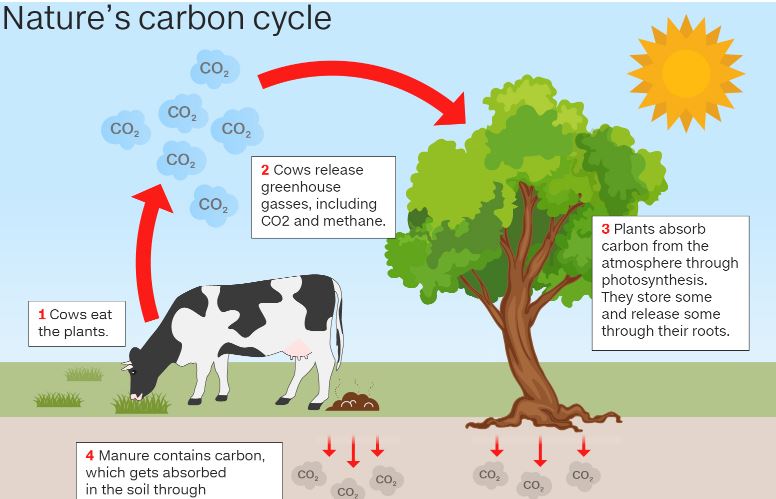

Conventional thinking says that cows are bad for climate change. After all, livestock contribute to around 14% of all global emissions. Researchers at UC Davis estimate that a single cow can belch around 220 pounds — roughly 100 kilograms — of methane each year. There are more than a billion cows on the planet, so that is a lot of (greenhouse) gas.

But cows didn’t evolve to sit in feedlots getting fat. Their wild relatives were out in the grassland in large numbers, just like on Slabbert’s farm.

Researchers at Texas A&M University led by Professor Richard Teague found that even moderately effective grazing systems put more carbon in the soil than the gasses cattle emit. Around 30% to 40% of the earth’s surface is natural grassland, and Teague says the potential for food security is immense.

«We studied farms and ranchers that had the highest soil carbon, and, with no exception, they managed their land following the principles where they were trying to do exactly what the bison did. They were trying to improve their land and their profits,» Teague said.

It’s all about the soil

The key to climate sustainable agriculture is the soil, because soil has an extraordinary ability to store carbon. There is more than three times as much carbon in the world’s soils than in the atmosphere, and scientists say that with better management, agricultural soils could absorb much more carbon in the future.

Even a change of a few percentage points would make a huge difference to the battle against the climate crisis. There is an upper limit to how much carbon soils can carry, but it can take decades to get to that point.

Publicado el 7/3/2020

Fuente: CNN